Echoplex

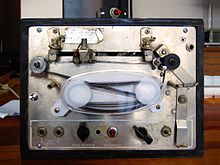

The Echoplex is a tape delay effect, first made in 1959. Designed by Mike Battle,[1] the Echoplex set a standard for the effect in the 1960s—it is still regarded as "the standard by which everything else is measured."[2] It was used by some of the most notable guitar players of the era; original Echoplexes are highly sought after.

The original tube Echoplex[edit]

Tape echoes work by recording sound on a magnetic tape, which is then played back; the tape speed or distance between heads determine the delay, while a feedback variable (where the delayed sound is delayed again) allows for a repetitive effect.[3] The predecessor of the Echoplex was a tape echo designed by Ray Butts in the 1950s, who built it into a guitar amplifier called the EchoSonic. He built fewer than seventy of them and could never keep up with the demand; they were used by players like Chet Atkins, Scotty Moore, and Carl Perkins.[4] Electronics technician Mike Battle copied the design and built it into a portable unit;[5] another version, however, states that Battle, working with a guitar player named Don Dixon from Akron, Ohio, perfected Dixon's original creation.[2]

The first Echoplex with vacuum tubes was marketed in 1961. Their big innovation was the moving head, which allowed the operator to change the delay time. In 1962, their patent was bought by a company called Market Electronics in Cleveland, Ohio. Market Electronics built the units and kept designers Battle and Dixon as consultants; they marketed the units through distributor Maestro, hence the name, Maestro Echoplex. In the 1950s, Maestro was a leader in vacuum tube technology. It had close ties with Gibson, and often manufactured amplifiers for Gibson. Later, Harris-Teller of Chicago took over production.[2] The first tube Echoplex had no number designation, but was retroactively designated the EP-1 after the unit received its first upgrade. The upgraded unit was designated the EP-2.[1] These two units set the standard for the delay effect, with their "warm, round, thick echo."[6] Two of Battle's improvements over earlier designs were key — the adjustable tape head, which allowed for variable delay, and a cartridge containing the tape, protecting it to retain sound quality.[2]

The Echoplex wasn't notable just for the delay, but also for the sound; it is "still a classic today, and highly desirable for a range of playing styles ... warm, rich, and full-bodied."[7] The delay could be turned off and the unit used as a filter, thanks to the sound of the vacuum tubes.

While Echoplexes were used mainly by guitar players (and the occasional bass player, such as Chuck Rainey, or trumpeter, such as Don Ellis or Miles Davis), many recording studios also used the Echoplex.[8] In addition, Andy Kulberg---the bassist for The Blues Project who doubled on flute---used an Echoplex with his self-electrified flute to play his second solo during the group's performance of "Flute Thing" at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival.

The solid-state Echoplex[edit]

EP-3[edit]

Market Electronics held off on using transistors while other companies made the transition. Nevertheless, in the late 1960s they set Battle and Dixon to the task of creating the first transistor version of their product. Once the two were satisfied, beginning in the 1970s, the solid-state Echoplex was offered by Maestro[6] and designated the EP-3, but Mike Battle, unhappy with the sound of the EP-3, sold his interest in the company.[1] This unit offered echo, sound-on-sound, and a number of minor convenience improvements. Having been produced from 1970 to 1991, this unit enjoyed the longest production run of all the Echoplex models. The FET-based preamp became legendary in its own right, with players like Eddie Van Halen, Brain May, Tom Verlaine, Andy Summers, and Jimmy Page using it with and without the echo on just to boost and color their sound. About the time of the public introduction of the EP-3, Maestro was taken over by Norlin Industries, then the parent company to Gibson Guitars.[2]

EP-4[edit]

In the mid-1970s Market created an upgrade to the EP-3, designated the EP-4, adding features such as an LED input meter and tone controls and dropping the sound-on-sound feature. The EP-4 has an added output buffer to help improve impedance matching with other equipment. A compressor board based on the CA3080 transconductance amplifier was added to the record circuit of both the EP-3 and EP-4 models for a short while after the EP-4 model was introduced and then the compressor board was dropped from both the EP-3 and EP-4 models. The EP-3 model was also offered for sale alongside the EP-4 model after the EP-4 was introduced.[9]

Battle's final consulting with Market yielded the EM-1 Groupmaster, which offered a four-channel input mixer section and a mono output section. Dissatisfied with the transistor-minded direction Maestro was taking, Butts left the company.[2] In the mid-1970s Maestro also created the ES-1 Sireko (pronounced "Sir-Echo"), a simplified, echo-only unit with a bin-loop cartridge system.[citation needed]

End of the brand[edit]

At the end of the 1970s, Norlin folded and their Maestro brand and Market Electronics was forced to find another distributor for their products. They found that distributor in Harris Teller, a Chicago musical wholesaler. Units built for Harris Teller carried an Echoplex badge that omitted the Maestro name. In 1984, Harris Teller bought out the Echoplex name and the stock of Echoplex parts from Market Electronics. Harris Teller used the back stock to assemble reissues of the EP-3, EP-4, and tube EP-2, which they designated the EP-6t. In 1991, the thirty-year run of electro-mechanical Echoplex production finally came to an end. Towards the middle of that decade the Echoplex brand was purchased by Gibson and applied to its line of digital looping units,[10][11] one of which was sold under the Oberheim brand as the Echoplex Digital Pro.[12]

Notable users[edit]

- Duane Allman[13]

- Chet Atkins[1]

- Tommy Bolin,[14][15][16] especially for the "ray-gun" effect heard on Billy Cobham's Spectrum[17]

- Wes Borland[18]

- Miles Davis[19]

- East Bay Ray[20]

- Don Ellis[21]

- Jerry Goldsmith[22][23]

- Eric Johnson[24][25]

- Esteban Jordan[26][27]

- Andy Kulberg (The Blues Project)

- John Martyn[28]

- Brian May[29]

- Steve Miller[30]

- Gary Moore[31]

- Jimmy Page[1][29]

- Chuck Rainey[32]

- Randy Rhoads[33]

- Joe Satriani[34]

- Neal Schon[35]

- Sonny Sharrock[36]

- Ace Frehley [37]

- Andy Summers[29]

- Eddie Van Halen[38][39]

- Joe Walsh[40][41]

- Keller Williams[42]

- Neil Young[43]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Cleveland, Barry (August 2008). "Passing Notes: Mike Battle". Guitar Player. 42 (8): 60.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Dregni, Michael (July 2012). "Echoplex EP-2". Vintage Guitar. pp. 54–56.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Milano, Dominic (1988). Multi-Track Recording. Hal Leonard. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-88188-552-1.

- ↑ Hunter, Dave (April 2012). "The Ray Butts EchoSonic". Vintage Guitar. pp. 46–48.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Hunter, Dave (2005). Guitar rigs: classic guitar & amp combinations. Hal Leonard. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-87930-851-3. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hunter, Dave (2004). Guitar effects pedals: the practical handbook. Hal Leonard. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-87930-806-3.

- ↑ Hunter, Dave (2005). Guitar rigs: classic guitar & amp combinations. Hal Leonard. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-87930-851-3.

- ↑ Hurtig, Brent (1988). Multi-track recording for musicians. Alfred. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-88284-355-1.

- ↑ Teagle, John (7 December 2004). "Echoplex: Roots of Echo, part IV". Vintage Guitar.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Looping: A talk with Matthias Grob". Gibson News. Gibson Labs, Gibson Guitar Corporation. December 13, 2004.

- ↑ Teagle, John (2004). "Roots of Echo Pt4". Vintage Guitar Magazine Online. 1 (1): 1. Retrieved 7 December 2004.)

- ↑ "NAMM '94 Report". Sound on Sound (March 1994).

- ↑ Gress, Jesse (April 2007). "10 Things You Gotta Do to Play Like Duane Allman". Guitar Player. pp. 110–17.

- ↑ Molenda, Mike; Les Paul (2007). The Guitar player book: 40 years of interviews, gear, and lessons from the world's most celebrated guitar magazine. Hal Leonard. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-87930-782-0.

- ↑ Méndez, Antonio (2007). Guía del pop y el rock, años 60: aloha PopRock. Editorial Visión Libros. p. 411. ISBN 978-84-9821-569-4.

- ↑ Ross, Michael (1998). Getting great guitar sounds: a non-technical approach to shaping your personal sound. Hal Leonard. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7935-9140-4.

- ↑ Blackett, Matt (October 2004). "The 50 Greatest Tones of All Time". Guitar Player. 38 (10): 44–66.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Newquist, H.P.; Rich Maloof (2004). The new metal masters. Hal Leonard. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-87930-804-9.

- ↑ Carr, Ian (1999). Miles Davis: the definitive biography. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-56025-241-2. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ Foley, Michael Stewart (2015). 33 1/3 Series - Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 55.

- ↑ Yurochko, Bob (2001). A Short History of Jazz. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8304-1595-3.

- ↑ Timm, Larry M. (2003). The soul of cinema: an appreciation of film music. Prentice Hall. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-13-030465-0.

- ↑ Cramer, Alfred W. (2009). Musicians and Composers of the 20th Century-Volume 2. Salem Press. p. 514. ISBN 978-1-58765-514-2.

- ↑ Prown, Pete; Lisa Sharken (2003). Gear Secrets of the Guitar Legends: How to Sound Like Your Favorite Players. Hal Leonard. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-87930-751-6.

- ↑ Fischer, Peter (2006). Masters of Rock Guitar 2: The New Generation, Volume 2. Mel Bay. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-89922-079-7.

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael (November 20, 2005). "Music Crossing Jordan". San Antonio Current. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael (August 14, 2010). "Steve 'Esteban' Jordan gave the accordion a new sound". Austin 360. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ↑ "John Martyn Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Campion, Chris (2009). Walking on the Moon: The Untold Story of the Police and the Rise of New Wave Rock. John Wiley and Sons. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-470-28240-3.

- ↑ Gress, Jesse (February 2011). "10 Things You Gotta Do To Play Like Steve Miller". Guitar Player. pp. 75–88.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Prown, Pete; Lisa Sharken (2003). Gear Secrets of the Guitar Legends: How to Sound Like Your Favorite Players. Hal Leonard. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-87930-751-6.

- ↑ Friedland, Ed (2005). The R&B Bass Masters: The Way They Play. Hal Leonard. pp. 17, 19. ISBN 978-0-87930-869-8.

- ↑ Gress, Jesse (May 2009). "10 Things You Gotta Do to Play Like Randy Rhoads". Guitar Player. 43 (5): 98–105.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Prown, Pete; Lisa Sharken (2003). Gear Secrets of the Guitar Legends: How to Sound Like Your Favorite Players. Hal Leonard. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-87930-751-6.

- ↑ Marshall, Wolf (April 2010). "Fretprints: Neal Schon". Vintage Guitar. 24 (6): 66–70.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Chambers, Jack (1998). Milestones: the music and times of Miles Davis. Da Capo. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-306-80849-4.

- ↑ http://www.premierguitar.com/articles/21374-ace-frehley-cosmic-space-invasion?page=3

- ↑ Newquist, H.P.; Rich Maloof (2004). The hard rock masters. Hal Leonard. pp. 31, 34. ISBN 978-0-87930-813-1.

- ↑ Gill, Chris (March 2007). "Some Kind of Monster". Guitar World. 28 (3): 56–62, 104. ISSN 1045-6295. Retrieved 2009-09-28. [dead link]

- ↑ Crockett, Jim (October 1972). "Joe Walsh, a Pro Replies". Guitar Player. p. 6.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Ten Things You Gotta Do to Play Like Joe Walsh". Guitar Player. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ↑ "Low-End Loop Master". Premier Guitar. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ↑ Obrecht, Jas (March 1992). "Neil Young's Guitar Equipment". Guitar Player. Retrieved 2012-08-13.