Canada

Canada is a country in North America.

Canada is second only to Russia in geographic area. Canada has by far the longest coastline of any country, 265,523 km or 16.2% of all the World's coastlines. Canada consists of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west and northward into the Arctic Ocean. Canada's common border with the United States to the south and northwest is the longest in the world. Despite its large area, its population is not very high, and its population density is amongst the lowest in the world. This is largely because much of its area is in the Arctic and very sparsely populated.

The land that is now Canada has been inhabited for millenia by American Indians descended from tribes that crossed the land bridge from Asia. It was explored by Europeans beginning with the Vikings under Leif Ericson and later by Basque fisherman seeking cod.

Beginning in the late 15th century, British and French expeditions explored and settled along the Atlantic coast and inland along the St. Lawrence River. Following the conquest of Quebec in 1763, during the French and Indian War, France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America. French settlers in Acadia were deported to Louisiana, while those in Quebec remained.

In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the United Kingdom. This widening autonomy was highlighted by the Statute of Westminster 1931 and culminated in the Canada Act 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the British parliament.

Canada is a federal state that is governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state. It is a bilingual nation with both English and French as official languages at the federal level. One of the world's most highly developed countries, Canada has a diversified economy that is reliant upon its abundant natural resources and upon trade – particularly with the United States, with which Canada has had a friendly and cooperative relationship. It is a member of the G7, G8, G20, NATO, OECD, WTO, Commonwealth of Nations, Francophonie, OAS, APEC, and UN. With the eighth-highest Human Development Index globally, it has one of the highest standards of living in the world.

Etymology[edit]

The name Canada comes from the Iroquois word, kanata, meaning "village" or "settlement".[1] In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec City region used the word to direct French explorer Jacques Cartier to the village of Stadacona.[2] Cartier later used the word Canada to refer not only to that particular village, but also the entire area subject to Donnacona (the chief at Stadacona); by 1545, European books and maps had begun referring to this region as Canada.[2]

In the 17th and early 18th century, Canada referred to the part of New France that lay along the Saint Lawrence River and the northern shores of the Great Lakes. The area was later split into two British colonies, Upper Canada and Lower Canada. They were re-unified as the Province of Canada in 1841.[3] Upon Confederation in 1867, the name Canada was adopted as the legal name for the new country, and Dominion (a term from Psalm 72:8) was conferred as the country's title.[4] As Canada asserted its political autonomy from the United Kingdom, the federal government increasingly used simply Canada on state documents and treaties, a change that was reflected in the renaming of the national holiday from Dominion Day to Canada Day in 1982.[5]

History[edit]

Aboriginal peoples[edit]

Archaeological and genetic studies support a human presence in the northern Yukon from 26,500 years ago, and in southern Ontario from 9,500 years ago.[6][7][8] Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are two of the earliest archaeological sites of human (Paleo-Indians) habitation in Canada.[9][10][11] The characteristics of Canadian Aboriginal societies included permanent settlements, agriculture, complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[12][13] Some of these cultures had faded by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and have been discovered through archaeological investigations.[14]

The aboriginal population is estimated to have been between 200,000[15] and two million in the late 15th century,[16] with a figure of 500,000 accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health.[17] Repeated outbreaks of European infectious diseases such as influenza, measles, and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity), combined with other effects of European contact, resulted in a forty to eighty percent aboriginal population decrease post-contact.[15] Aboriginal peoples in Canada include the First Nations,[18] Inuit,[19] and Métis.[20] The Métis are a mixed-blood people who originated in the mid-17th century when First Nation and Inuit married European settlers.[21] The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during the colonization period.[22]

European colonization[edit]

European colonization began when Norsemen settled briefly at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland around 1000.[23] No further European exploration occurred until 1497, when Italian seafarer John Cabot explored Canada's Atlantic coast for England.[24] Basque and Portuguese mariners established seasonal whaling and fishing outposts along the Atlantic coast.[25] In 1534 Jacques Cartier explored the Saint Lawrence River for France.[26]

In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed St. John's, Newfoundland as the first North American English colony by royal prerogative of Queen Elizabeth I.[27] French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in 1603 and established the first permanent European settlements at Port Royal in 1605 and Quebec City in 1608. Among French colonists of New France, Canadiens extensively settled the Saint Lawrence River valley and Acadians settled the present-day Maritimes, while fur traders and Catholic missionaries explored the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, and the Mississippi watershed to Louisiana. The Beaver Wars broke out over control of the North American fur trade.[26]

The English established additional colonies in Cupids and Ferryland, Newfoundland beginning in 1610 and soon after founded the Thirteen Colonies to the south.[25] A series of four French and Indian Wars erupted between 1689 and 1763.[26] Mainland Nova Scotia came under British rule with the Treaty of Utrecht (1713); the Treaty of Paris (1763) ceded Canada and most of New France to Britain after the Seven Years' War.[28]

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 carved the Province of Quebec out of New France and annexed Cape Breton Island to Nova Scotia.[5] St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony in 1769.[29] To avert conflict in Quebec, the British passed the Quebec Act of 1774, expanding Quebec's territory to the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley. It re-established the French language, Catholic faith, and French civil law there. This angered many residents of the Thirteen Colonies and helped to fuel the American Revolution.[5]

The Treaty of Paris (1783) recognized American independence and ceded territories south of the Great Lakes to the United States. New Brunswick was split from Nova Scotia as part of a reorganization of Loyalist settlements in the Maritimes. To accommodate English-speaking Loyalists in Quebec, the Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the province into French-speaking Lower Canada (later Quebec) and English-speaking Upper Canada (later Ontario), granting each its own elected legislative assembly.[30]

The Canadas were the main front in the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain. Following the war, large-scale immigration to Canada from Britain and Ireland began in 1815.[16] From 1825 to 1846, 626,628 European immigrants landed at Canadian ports.[32] Between one-quarter and one-third of all Europeans who immigrated to Canada before 1891 died of infectious diseases.[15]

The desire for responsible government resulted in the aborted Rebellions of 1837. The Durham Report subsequently recommended responsible government and the assimilation of French Canadians into English culture.[5] The Act of Union 1840 merged The Canadas into a united Province of Canada. Responsible government was established for all British North American provinces by 1849.[33] The signing of the Oregon Treaty by Britain and the United States in 1846 ended the Oregon boundary dispute, extending the border westward along the 49th parallel. This paved the way for British colonies on Vancouver Island (1849) and in British Columbia (1858).[34]

Confederation and expansion[edit]

Following several constitutional conferences, the Constitution Act, 1867 officially proclaimed Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[35][36][37] Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories, where the Métis' grievances ignited the Red River Rebellion and the creation of the province of Manitoba in July 1870.[38] British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had united in 1866) and Prince Edward Island joined the Confederation in 1871 and 1873, respectively.[39] Prime Minister John A. Macdonald and his Conservative government established a National Policy of tariffs to protect nascent Canadian manufacturing industries.[37]

To open the West, the government sponsored construction of three transcontinental railways (including the Canadian Pacific Railway), opened the prairies to settlement with the Dominion Lands Act, and established the North-West Mounted Police to assert its authority over this territory.[40][41] In 1898, after the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, the Canadian government created the Yukon Territory. Under Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, continental European immigrants settled the prairies, and Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.[39]

Early 20th century[edit]

Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the Confederation Act, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought Canada into World War I. Volunteers sent to the Western Front later became part of the Canadian Corps. The Corps played a substantial role in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and other major battles of the war.[42] Out of approximately 625,000 who served, about 60,000 were killed and another 173,000 were wounded.[43] The Conscription Crisis of 1917 erupted when conservative Prime Minister Robert Borden brought in compulsory military service over the objection of French-speaking Quebecers. In 1919, Canada joined the League of Nations independently of Britain and,[42] the Statute of Westminster 1931 affirmed Canada's independence.[44]

The Great Depression brought economic hardship throughout Canada. In response, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Alberta and Saskatchewan enacted many measures of a welfare state (as pioneered by Tommy Douglas) into the 1940s and 1950s.[45] Canada declared war on Germany independently during World War II under Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, three days after Britain. The first Canadian Army units arrived in Britain in December 1939.[42]

Canadian troops played important roles in the failed 1942 Dieppe Raid, the Allied invasion of Italy, the Normandy landings, the Battle of Normandy, and the Battle of the Scheldt in 1944.[42] Canada provided asylum for the monarchy of the Netherlands while that country was occupied, and is credited by the country for leadership and major contributions to its liberation from Nazi Germany.[46] The Canadian economy boomed as industry manufactured military materiel for Canada, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union.[42] Despite another Conscription Crisis in Quebec, Canada finished the war with a large army and strong economy.[47]

Modern times[edit]

Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) joined Canada in 1949.[48] Canada's post-war economic growth, combined with the policies of successive Liberal governments, led to the emergence of a new Canadian identity, marked by the adoption of the current Maple Leaf Flag in 1965,[49] the implementation of official bilingualism (English and French) in 1969,[50] and official multiculturalism in 1971.[51] There was also the founding of socially democratic programmes, such as Medicare, the Canada Pension Plan, and Canada Student Loans, though provincial governments, particularly Quebec and Alberta, opposed many of these as incursions into their jurisdictions.[52] Finally, another series of constitutional conferences resulted in the 1982 patriation of Canada's constitution from the United Kingdom, concurrent with the creation of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[53] In 1999, Nunavut became Canada's third territory after a series of negotiations with the federal government.[54]

At the same time, Quebec underwent profound social and economic changes through the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, giving birth to a modern nationalist movement. The radical Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) ignited the October Crisis in 1970.[55] The sovereignist Parti Québécois was elected in 1976 and organized an unsuccessful referendum on sovereignty-association in 1980. Attempts to accommodate Quebec nationalism constitutionally through the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990.[56] This led to the formation of the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and invigoration of the Reform Party of Canada in the West.[57][58] A second referendum followed in 1995, in which sovereignty was rejected by a slimmer margin of just 50.6 to 49.4 percent. In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that unilateral secession by a province would be unconstitutional, and the Clarity Act was passed by parliament, outlining the terms of a negotiated departure from Confederation.[56]

In addition to the issues of Quebec sovereignty, a number of crises shook Canadian society in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the explosion of Air India Flight 182 in 1985, the largest mass murder in Canadian history;[59] the École Polytechnique massacre in 1989, a university shooting targeting female students;[60] and the Oka Crisis in 1990,[61] the first of a number of violent confrontations between the government and Aboriginal groups.[62] Canada also joined the Gulf War in 1990 as part of a US-led coalition force, and was active in several peacekeeping missions in the late 1990s.[63] It sent troops to Afghanistan in 2001, but declined to send forces to Iraq when the US invaded in 2003.[64]

Geography[edit]

Canada occupies a major northern portion of North America, sharing the land borders with the contiguous United States to the south and the US state of Alaska to the northwest, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west; to the north lies the Arctic Ocean.[65][66] By total area (including its waters), Canada is the second-largest country in the world, after Russia. By land area, Canada ranks fourth.[66]

The country lies between latitudes 41° and 84°N, and longitudes 52° and 141°W. Since 1925, Canada has claimed the portion of the Arctic between 60° and 141°W longitude,[67] but this claim is not universally recognized. The northernmost settlement in Canada (and in the world) is Canadian Forces Station Alert on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island – latitude 82.5°N – 817 kilometres (450 nautical miles, 508 miles) from the North Pole.[68] Much of the Canadian Arctic is covered by ice and permafrost. Canada also has the longest coastline in the world: 202,080 kilometres (125,570 mi).[66]

Since the last glacial period Canada has consisted of eight distinct forest regions, including extensive boreal forest on the Canadian Shield.[70] Canada has more lakes than any other country, containing much of the world's fresh water.[71] There are also fresh-water glaciers in the Canadian Rockies and the Coast Mountains. Canada is geologically active, having many earthquakes and potentially active volcanoes, notably Mount Meager, Mount Garibaldi, Mount Cayley, and the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.[72] The volcanic eruption of Tseax Cone in 1775 caused a catastrophic disaster, killing 2,000 Nisga'a people and destroying their village in the Nass River valley of northern British Columbia; the eruption produced a 22.5-kilometre (14.0 mi) lava flow, and according to legend of the Nisga'a people, it blocked the flow of the Nass River.[73]

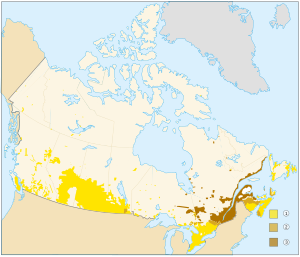

The population density, 3.3 inhabitants per square kilometre (8.5/sq mi), is among the lowest in the world. The most densely populated part of the country is the Quebec City – Windsor Corridor, situated in Southern Quebec and Southern Ontario along the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River.[74]

Average winter and summer high temperatures across Canada vary according to the location. Winters can be harsh in many regions of the country, particularly in the interior and Prairie provinces, which experience a continental climate, where daily average temperatures are near −15 °C (5 °F) but can drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) with severe wind chills.[75] In noncoastal regions, snow can cover the ground almost six months of the year (more in the north). Coastal British Columbia has a temperate climate, with a mild and rainy winter. On the east and west coasts, average high temperatures are generally in the low 20s °C (70s °F), while between the coasts, the average summer high temperature ranges from 25 to 30 °C (77 to 86 °F), with occasional extreme heat in some interior locations exceeding 40 °C (104 °F).[76]Template:Clearright

Government and politics[edit]

Canada has strong democratic traditions upheld through a parliamentary system within the construct of constitutional monarchy; the monarchy of Canada is the foundation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.[77][78][79][80] The sovereign is Queen Elizabeth II, who also serves as head of state of 15 other Commonwealth countries and each of Canada's ten provinces and resides predominantly in the United Kingdom. As such, the Queen's representative, the Governor General of Canada (presently David Lloyd Johnston), carries out most of the federal royal duties in Canada.[81][82]

The direct participation of the royal and viceroyal figures in areas of governance is limited;[79][83][84] in practice, their use of the executive powers is directed by the Cabinet, a committee of ministers of the Crown responsible to the elected House of Commons and chosen and headed by the Prime Minister of Canada (presently Stephen Harper[85]), the head of government. To ensure the stability of government, the governor general will usually appoint as prime minister the person who is the current leader of the political party that can obtain the confidence of a plurality in the House of Commons.[86] The Prime Minister's Office (PMO) is thus one of the most powerful institutions in government, initiating most legislation for parliamentary approval and selecting for appointment by the Crown, besides the aforementioned, the governor general, lieutenant governors, senators, federal court judges, and heads of Crown corporations and government agencies.[83] The leader of the party with the second-most seats usually becomes the Leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition (presently Nycole Turmel) and is part of an adversarial parliamentary system intended to keep the government in check.[87]

Each of the 308 Members of Parliament in the House of Commons is elected by simple plurality in an electoral district or riding. General elections must be called by the governor general, on the advice of the prime minister, within four years of the previous election, or may be triggered by the government losing a confidence vote in the House.[88] The 105 members of the Senate, whose seats are apportioned on a regional basis, serve until age 75.[89] Five parties had representatives elected to the federal parliament in the 2011 elections: the Conservative Party of Canada (governing party), the New Democratic Party (the Official Opposition), the Liberal Party of Canada, the Bloc Québécois, and the Green Party of Canada. The list of historical parties with elected representation is substantial.

Canada's federal structure divides government responsibilities between the federal government and the ten provinces. Provincial legislatures are unicameral and operate in parliamentary fashion similar to the House of Commons.[84] Canada's three territories also have legislatures, but these are not sovereign and have fewer constitutional responsibilities than the provinces and with some structural differences.[90][91]

Law[edit]

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of the country, and consists of written text and unwritten conventions. The Constitution Act, 1867 (known as the British North America Act prior to 1982) affirmed governance based on parliamentary precedent and divided powers between the federal and provincial governments; the Statute of Westminster 1931 granted full autonomy; and the Constitution Act, 1982, ended all legislative ties to the UK, added a constitutional amending formula, and added the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees basic rights and freedoms that usually cannot be overridden by any government – though a notwithstanding clause allows the federal parliament and provincial legislatures to override certain sections of the Charter for a period of five years.[92]

Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful. The Crown and Aboriginal peoples began interactions during the European colonialization period. Numbered Treaties, the Indian Act, the Constitution Act of 1982, and case laws were established.[93] A series of eleven treaties were signed between Aboriginals in Canada and the reigning Monarch of Canada from 1871 to 1921.[94] These treaties are agreements with the Government of Canada administered by Canadian Aboriginal law and overseen by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The role of the treaties was reaffirmed by Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982, which "recognizes and affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights".[93] These rights may include provision of services such as health care, and exemption from taxation.[95] The legal and policy framework within which Canada and First Nations operate was further formalized in 2005, through the First Nations–Federal Crown Political Accord.[93]

Canada's judiciary plays an important role in interpreting laws and has the power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court and final arbiter and has been led by the Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, P.C. (the first female Chief Justice) since 2000.[96] Its nine members are appointed by the governor general on the advice of the Prime Minister and Minister of Justice. All judges at the superior and appellate levels are appointed after consultation with nongovernmental legal bodies. The federal cabinet also appoints justices to superior courts at the provincial and territorial levels.[97]

Common law prevails everywhere except in Quebec, where civil law predominates. Criminal law is solely a federal responsibility and is uniform throughout Canada.[98] Law enforcement, including criminal courts, is a provincial responsibility, but in rural areas of all provinces except Ontario and Quebec, policing is contracted to the federal Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[99]

Foreign relations and military[edit]

Canada and the United States share the world's longest undefended border, co-operate on military campaigns and exercises, and are each other's largest trading partner.[100] Canada nevertheless has an independent foreign policy, most notably maintaining full relations with Cuba and declining to officially participate in the Iraq War. Canada also maintains historic ties to the United Kingdom and France and to other former British and French colonies through Canada's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations and the Francophonie.[101] Canada is noted for having a positive relationship with the Netherlands, owing, in part, to its contribution to the Dutch liberation.[46]

Canada currently employs a professional, volunteer military force of over 67,000 regular and approximately 43,000 reserve personnel including supplementary reserves.[102] The unified Canadian Forces (CF) comprise the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy, and Royal Canadian Air Force.

Strong attachment to the British Empire and Commonwealth led to major participation in British military efforts in the Second Boer War, World War I and World War II. Since then, Canada has been an advocate for multilateralism, making efforts to resolve global issues in collaboration with other nations.[103][104] Canada was a founding member of the United Nations in 1945 and of NATO in 1949. During the Cold War, Canada was a major contributor to UN forces in the Korean War and founded the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in cooperation with the United States to defend against potential aerial attacks from the Soviet Union.[105]

During the Suez Crisis of 1956, future Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson eased tensions by proposing the inception of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force, for which he was awarded the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize.[106] As this was the first UN peacekeeping mission, Pearson is often credited as the inventor of the concept. Canada has since served in 50 peacekeeping missions, including every UN peacekeeping effort until 1989,[42] and has since maintained forces in international missions in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia, and elsewhere; Canada has sometimes faced controversy over its involvement in foreign countries, notably in the 1993 Somalia Affair.[107]

Canada joined the Organization of American States (OAS) in 1990 and hosted the OAS General Assembly in Windsor, Ontario, in June 2000 and the third Summit of the Americas in Quebec City in April 2001.[108] Canada seeks to expand its ties to Pacific Rim economies through membership in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC).[109]

In 2001, Canada had troops deployed to Afghanistan as part of the US stabilization force and the UN-authorized, NATO-commanded International Security Assistance Force. Starting in July 2011, Canada began withdrawing its troops from Afghanistan. The mission had cost 157 soldiers, one diplomat, two aid workers, and one journalist their lives,[110] with an approximate cost of C$11.3 billion[111] Canada and the US continue to integrate state and provincial agencies to strengthen security along the Canada-United States border through the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative.[112]

In February 2007, Canada, Italy, Britain, Norway, and Russia announced their funding commitments to launch a $1.5 billion project to help develop vaccines they said could save millions of lives in poor nations, and called on others to join them.[113] In August 2007, Canada's territorial claims in the Arctic were challenged after a Russian underwater expedition to the North Pole; Canada has considered that area to be sovereign territory since 1925.[114] In July 2010 the largest purchase in Canadian military history, totaling C$9 billion for the acquisition of 65 F-35 fighters was announced by the federal government.[115]

Provinces and territories[edit]

Canada is a federation composed of ten provinces and three territories. In turn, these may be grouped into regions: Western Canada, Central Canada, Atlantic Canada, and Northern Canada (Eastern Canada refers to Central Canada and Atlantic Canada together). Provinces have more autonomy than territories. The provinces are responsible for most of Canada's social programs (such as health care, education, and welfare) and together collect more revenue than the federal government, an almost unique structure among federations in the world. Using its spending powers, the federal government can initiate national policies in provincial areas, such as the Canada Health Act; the provinces can opt out of these, but rarely do so in practice. Equalization payments are made by the federal government to ensure that reasonably uniform standards of services and taxation are kept between the richer and poorer provinces.[116] Template:Canada image map Template:Clearleft

Economy[edit]

Canada is one of the world's wealthiest nations, with a high per-capita income. It is a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the G8, and is one of the world's top ten trading nations.[117] Canada is a mixed economy, ranking above the US and most western European nations on the Heritage Foundation's index of economic freedom.[118] The largest foreign importers of Canadian goods are the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan.[119]

In the past century, the growth of the manufacturing, mining, and service sectors has transformed the nation from a largely rural economy to a more industrial and urban one. Like other First World nations, the Canadian economy is dominated by the service industry, which employs about three quarters of Canadians.[120] Canada is unusual among developed countries in the importance of its primary sector, in which the logging and petroleum industries are two of the most important.[121]

Canada is one of the few developed nations that are net exporters of energy.[122] Atlantic Canada has vast offshore deposits of natural gas, and Alberta has large oil and gas resources. The immense Athabasca oil sands give Canada the world's second-largest oil reserves, behind Saudi Arabia.[123]

Canada is one of the world's largest suppliers of agricultural products; the Canadian Prairies are one of the most important producers of wheat, canola, and other grains.[124] Canada is the largest producer of zinc and uranium, and is a global source of many other natural resources, such as gold, nickel, aluminum, and lead.[122] Many towns in northern Canada, where agriculture is difficult, are sustainable because of nearby mines or sources of timber. Canada also has a sizable manufacturing sector centred in southern Ontario and Quebec, with automobiles and aeronautics representing particularly important industries.[125]

Economic integration with the United States has increased significantly since World War II. The Automotive Products Trade Agreement of 1965 opened the borders to trade in the auto manufacturing industry. In the 1970s, concerns over energy self-sufficiency and foreign ownership in the manufacturing sectors prompted Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's Liberal government to enact the National Energy Program (NEP) and the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA).[126]

In the 1980s, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservatives abolished the NEP and changed the name of FIRA to "Investment Canada" in order to encourage foreign investment.[127] The Canada – United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of 1988 eliminated tariffs between the two countries, while the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) expanded the free-trade zone to include Mexico in the 1990s.[124] In the mid-1990s, the Liberal government under Jean Chrétien began to post annual budgetary surpluses and steadily paid down the national debt.[128] The global financial crisis of 2008 caused a recession, which could increase the country's unemployment rate to 10 percent.[129] In 2008, Canada's imported goods were worth over $442.9 billion, of which $280.8 billion was from the United States, $11.7 billion from Japan, and $11.3 billion from the United Kingdom.[119] The country’s 2009 trade deficit totaled C$4.8 billion, compared with a C$46.9 billion surplus in 2008.[130]

As of October 2009, Canada's national unemployment rate was 8.6 percent. Provincial unemployment rates vary from a low of 5.8 percent in Manitoba to a high of 17 percent in Newfoundland and Labrador.[131] Between October 2008, and October 2010, the Canadian labour market lost 162,000 full-time jobs and a total of 224,000 permanent jobs.[132] Canada's federal debt is estimated to be $566.7 billion for 2010–11, up from $463.7 billion in 2008–09.[133] Canada’s net foreign debt rose by $41-billion to $194-billion in the first quarter of 2010.[134]

Science and technology[edit]

Canada is an industrial nation with a highly developed science and technology sector. Nearly 1.88 percent of Canada's GDP is allocated to research & development (R&D).[135] The country has ten Nobel laureates in physics, chemistry and medicine.[136] Canada ranks twelfth in the world for Internet usage with 28.0 million users, 84.3 percent of the total population.[137]

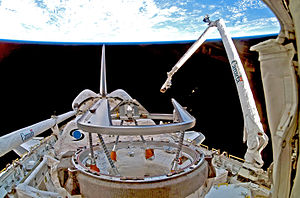

The Canadian Space Agency conducts space, planetary, and aviation research, and develops rockets and satellites. In 1984, Marc Garneau became Canada's first astronaut, serving as payload specialist of STS-41-G. Canada was ranked third among 20 top countries in space sciences.[138] Canada is a participant in the International Space Station and one of the world's pioneers in space robotics with the Canadarm, Canadarm2 and Dextre. Since the 1960s, Canada Aerospace Industries have designed and built 10 satellites, including Radarsat-1, Radarsat-2 and MOST.[139] Canada also produced one of the most successful sounding rockets, the Black Brant; over 1000 have been launched since they were initially produced in 1961.[140] Universities across Canada are working on the first domestic landing spacecraft: the Northern Light, designed to search for life on Mars and investigate Martian electromagnetic radiation environment and atmospheric properties. If the Northern Light is successful, Canada will be the third country to land on another planet.[141]

Demographics[edit]

Script error: No such module "Historical populations".

The Canada 2006 Census counted a total population of 31,612,897, an increase of 5.4 percent since 2001.[142] Population in Canada increased from 1990 to 2008 with 5.6 million and 20.4 % growth in population compared to 21,7 % growth in the USA and 31.2 % growth in Mexico. According to the OECD/World Bank population statistics between 1990–2008 the world population growth was 27 % and 1,423 million persons.[143] Population growth is from immigration and, to a lesser extent, natural growth. About four-fifths of Canada's population lives within 150 kilometres (93 mi) of the United States border.[144] The majority of Canadians (approximately 80%) live in urban areas concentrated in the Quebec City – Windsor Corridor, the BC Lower Mainland, and the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor in Alberta.[145] In common with many other developed countries, Canada is experiencing a demographic shift towards an older population, with more retirees and fewer people of working age. In 2006, the average age of the population was 39.5 years.[146]

According to the 2006 census, the largest self-reported ethnic origin is Canadian (32%), followed by English (21%), French (15.8%), Scottish (15.1%), Irish (13.9%), German (10.2%), Italian (4.6%), Chinese (4.3%), First Nations (4.0%), Ukrainian (3.9%), and Dutch (3.3%).[147] There are 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands encompassing 1,172,790 people.[148]

Canada's Aboriginal population is growing at almost twice the national rate, and 3.8 percent of Canada's population claimed aboriginal identity in 2006. Another 16.2 percent of the population belonged to a non-aboriginal visible minority.[149] The largest visible minority groups in Canada are South Asian (4.0%), Chinese (3.9%) and Black (2.5%). Between 2001 and 2006, the visible minority population rose by 27.2 percent.[150] In 1961, less than two percent of Canada's population (about 300,000 people) could be classified as belonging to a visible minority group and less than 1% as aboriginal.[151] As of 2007, almost one in five Canadians (19.8%) were foreign-born. Nearly 60 percent of new immigrants come from Asia (including the Middle East).[152] The leading emigrating countries to Canada were China, Philippines and India.[153] By 2031, one in three Canadians could belong to a visible minority group.[154]

Canada has one of the highest per-capita immigration rates in the world,[155] driven by economic policy and family reunification, and is aiming for between 240,000 and 265,000 new permanent residents in 2011, the same number of immigrants as in recent years.[156] New immigrants settle mostly in major urban areas like Toronto and Vancouver.[157] Canada also accepts large numbers of refugees.[158] The country resettles over one in 10 of the world’s refugees.[159]

According to the 2001 census, 77.1 percent of Canadians identify as being Christians; of this, Catholics make up the largest group (43.6% of Canadians). The largest Protestant denomination is the United Church of Canada (9.5% of Canadians), followed by the Anglicans (6.8%), Baptists (2.4%), Lutherans (2%), and other Christians (4.4%). About 16.5 percent of Canadians declare no religious affiliation, and the remaining 6.3 percent are affiliated with non-Christian religions, the largest of which is Islam (2.0%), followed by Judaism (1.1%).[160]

Canadian provinces and territories are responsible for education. Each system is similar, while reflecting regional history, culture and geography. The mandatory school age ranges between 5–7 to 16–18 years,[161] contributing to an adult literacy rate of 99 percent.[66] In 2002, 43 percent of Canadians aged 25 to 64 possessed a post-secondary education; for those aged 25 to 34, the rate of post-secondary education reached 51 percent.[162] Template:Largest Metropolitan Areas of Canada

Language[edit]

Canada's two official languages are English and French. Official bilingualism is defined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Official Languages Act, and Official Language Regulations; it is applied by the Commissioner of Official Languages. English and French have equal status in federal courts, Parliament, and in all federal institutions. Citizens have the right, where there is sufficient demand, to receive federal government services in either English or French, and official-language minorities are guaranteed their own schools in all provinces and territories.[163]

English and French are the first languages of 59.7 and 23.2 percent of the population respectively. Approximately 98 percent of Canadians speak English or French: 57.8% speak English only, 22.1% speak French only, and 17.4% speak both.[164] English and French Official Language Communities, defined by First Official Language Spoken, constitute 73.0 and 23.6 percent of the population respectively.[165]

The Charter of the French Language makes French the official language in Quebec.[166] Although more than 85 percent of French-speaking Canadians live in Quebec, there are substantial Francophone populations in Ontario, Alberta, and southern Manitoba; Ontario has the largest French-speaking population outside Quebec.[167] New Brunswick, the only officially bilingual province, has a French-speaking Acadian minority constituting 33 percent of the population. There are also clusters of Acadians in southwestern Nova Scotia, on Cape Breton Island, and through central and western Prince Edward Island.[168]

Other provinces have no official languages as such, but French is used as a language of instruction, in courts, and for other government services in addition to English. Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec allow for both English and French to be spoken in the provincial legislatures, and laws are enacted in both languages. In Ontario, French has some legal status but is not fully co-official.[169] There are 11 Aboriginal language groups, made up of more than 65 distinct dialects.[170] Of these, only Cree, Inuktitut and Ojibway have a large enough population of fluent speakers to be considered viable to survive in the long term.[171] Several aboriginal languages have official status in the Northwest Territories.[172] Inuktitut is the majority language in Nunavut, and one of three official languages in the territory.[173]

Over six million people in Canada list a non-official language as their mother tongue. Some of the most common non-official first languages include Chinese (mainly Cantonese; 1,012,065 first-language speakers), Italian (455,040), German (450,570), Punjabi (367,505) and Spanish (345,345).[174] English and French are the languages most spoken at home by 68.3 percent and 22.3 percent of the population respectively.[175]

Culture[edit]

Canada has a diverse makeup of nationalities and cultures, and has constitutional protection for policies that promote multiculturalism.[176] In Quebec, cultural identity is strong, and many French-speaking commentators speak of a culture of Quebec as distinguished from English Canadian culture;[177] however, as a whole Canada is a cultural mosaic – a collection of several regional, aboriginal, and ethnic subcultures.[178] Government policies such as publicly-funded health care, higher taxation to distribute wealth, outlawing capital punishment, strong efforts to eliminate poverty, an emphasis on multiculturalism, stricter gun control, and legalization of same-sex marriage are social indicators of how Canada's political and cultural evolution differs from that of the United States.[179]

Historically Canada has been influenced by British, French, and aboriginal cultures and traditions. Through their culture, language, art and music, aboriginals continue to influence the Canadian identity.[180] Many Canadians value multiculturalism and see Canada as being inherently multicultural.[53] American media and entertainment are popular, if not dominant, in English Canada; conversely, many Canadian cultural products and entertainers are successful in the United States and worldwide.[181] Many cultural products are marketed toward a unified "North American" or global market. The creation and preservation of distinctly Canadian culture are supported by federal government programs, laws, and institutions such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the National Film Board of Canada, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission.[182]

Canadian visual art has been dominated by Tom Thomson – Canada's most famous painter – and by the Group of Seven. Thomson's brief career painting Canadian landscapes spanned just a decade up to his death in 1917 at age 39.[183] The Group were painters with a nationalistic and idealistic focus, who first exhibited their distinctive works in May 1920. Though referred to as having seven members, five artists – Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley – were responsible for articulating the Group's ideas. They were joined briefly by Frank Johnston, and by commercial artist Franklin Carmichael. A. J. Casson became part of the Group in 1926.[184] Associated with the Group was another prominent Canadian artist, Emily Carr, known for her landscapes and portrayals of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast.[185]

The Canadian music industry has produced internationally renowned composers, musicians and ensembles.[186] Canada's music broadcasting is regulated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences administers Canada's music industry awards, the Juno Awards, which commenced in 1970.[187] The national anthem of Canada O Canada adopted in 1980, was originally commissioned by the Lieutenant Governor of Quebec, the Honourable Théodore Robitaille, for the 1880 St. Jean-Baptiste Day ceremony.[188] Calixa Lavallée wrote the music, which was a setting of a patriotic poem composed by the poet and judge Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier. The text was originally only in French, before it was translated to English in 1906.[189]

Canada's official national sports are ice hockey and lacrosse.[190] Hockey is a national pastime and the most popular spectator sport in the country. It is also the sport most played by Canadians, with 1.65 million participants in 2004. Seven of Canada's eight largest metropolitan areas – Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg – have franchises in the National Hockey League (NHL), and there are more Canadian players in the NHL than from all other countries combined. Other popular spectator sports include curling and football; the latter is played professionally in the Canadian Football League (CFL). Golf, baseball, skiing, soccer, cricket, volleyball, and basketball are widely played at youth and amateur levels, but professional leagues and franchises are not widespread.[191]

Canada has hosted several high-profile international sporting events, including the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, and the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup. Canada was the host nation for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler, British Columbia.[192]

Canada's national symbols are influenced by natural, historical, and Aboriginal sources. The use of the maple leaf as a Canadian symbol dates to the early 18th century. The maple leaf is depicted on Canada's current and previous flags, on the penny, and on the Arms of Canada.[193] Other prominent symbols include the beaver, Canada Goose, Common Loon, the Crown, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police,[193] and more recently, the totem pole and Inuksuk.[194]

References[edit]

- ↑ "Origin of the Name, Canada". Canadian Heritage. 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Maura, Juan Francisco (2009). "Nuevas aportaciones al estudio de la toponimia ibérica en la América Septentrional en el siglo XVI". Bulletin of Spanish Studies. 86 (5): 577–603. doi:10.1080/14753820902969345.

- ↑ Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories of Canadian Place Names (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 0802082939.

- ↑ O'Toole, Roger (2009). "Dominion of the Gods: Religious continuity and change in a Canadian context". In Hvithamar, Annika; Warburg, Margit; Jacobsen, Brian Arly (ed.). Holy nations and global identities : civil religion, nationalism, and globalisation. Brill. p. 137. ISBN 9789004178281.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Buckner, Philip, ed. (2008). Canada and the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–40, 56–59, 114, 124–125. ISBN 019927164X.

- ↑ "Y-Chromosome Evidence for Differing Ancient Demographic Histories in the Americas" (PDF). University College London 73:524–539. 2003. doi:10.1086/377588. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Cinq-Mars, J (2001). "On the significance of modified mammoth bones from eastern Beringia" (PDF). The World of Elephants – International Congress, Rome. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Wright, JV (September 27, 2009). "A History of the Native People of Canada: Early and Middle Archaic Complexes". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Griebel, Ron. "The Bluefish Caves". Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Beringia: humans were here". Montreal Gazette. May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ↑ Cinq-Mars, Jacques (2001). "Significance of the Bluefish Caves in Beringian Prehistory". Canadian Museum of Civilization. p. 2. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Hayes, Derek (2008). Canada : an illustrated history. Douglas & Mcintyre. pp. 7, 13. ISBN 9781553652595.

- ↑ Macklem, Patrick (2001). Indigenous difference and the Constitution of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 170. ISBN 0802041957.

- ↑ Sonneborn, Liz (January 2007). Chronology of American Indian History. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–12. ISBN 9780816067701.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Wilson, Donna M (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 9781551118734. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 16.0 16.1 Thornton, Russell (2000). "Population history of Native North Americans". In Haines, Michael R; Steckel, Richard Hall (ed.). A population history of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13, 380. ISBN 0521496667.

My 7+ million estimate for the area north of present-day Mexico includes...somewhat more than 2 million for present-day Canada, Alaska, and Greenland combined.

CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ Bailey, Garrick Alan (2008). Handbook of North American Indians: Indians in contemporary society. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 0160803888.

- ↑ "Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage: Culture". Canadian Museum of Civilization. May 12, 2006. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "ICC Charter". Inuit Circumpolar Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "In the Kawaskimhon Aboriginal Moot Court Factum of the Federal Crown Canada". University of Manitoba Faculty of Law. 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-19. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "What to Search: Topics". Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups. Library and Archives Canada. May 27, 2005. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Tanner, Adrian (1999). "3. Innu-Inuit 'Warfare'". Innu Culture. Department of Anthropology, Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Reeves, Arthur Middleton (2009). The Norse Discovery of America. BiblioLife. p. 82. ISBN 9780559054006.

- ↑ "John Cabot's voyage of 1498". Memorial University of Newfoundland. 2000. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hornsby, Stephen J (2005). British Atlantic, American frontier : spaces of power in early modern British America. University Press of New England. pp. 14, 18–19, 22–23. ISBN 9781584654278.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Morton, Desmond (2001). A Short History of Canada (6th ed.). McClelland & Stewart. pp. 9–19, 33, 89–104. ISBN 0771065094.

- ↑ "Gilbert (Gylberte, Jilbert), Sir Humphrey". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. University of Toronto. May 2, 2005. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ↑ Allaire, Gratien (May 2007). "From "Nouvelle-France" to "Francophonie canadienne": a historical survey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (185): 25–52. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.024.

- ↑ Hicks, Bruce M (March 2010). "Use of Non-Traditional Evidence: A Case Study Using Heraldry to Examine Competing Theories for Canada's Confederation". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 23 (1): 87–117. doi:10.3828/bjcs.2010.5.

- ↑ McNairn, Jeffrey L (2000). The capacity to judge. University of Toronto Press. p. 24. ISBN 0802043607.

- ↑ This is a photograph taken in 1885 of the now-destroyed 1884 painting.

- ↑ "Immigration History of Canada". Marianopolis College. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Romney, Paul (Spring 1989). "From Constitutionalism to Legalism: Trial by Jury, Responsible Government, and the Rule of Law in the Canadian Political Culture". Law and History Review. University of Illinois Press. 7 (1): 128.

- ↑ Evenden, Leonard J (1992). "The Pacific Coast Borderland and Frontier". In Janelle, Donald G (ed.). Geographical snapshots of North America. Guilford Press. p. 52. ISBN 0898620309. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Territorial evolution". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Canada: History". Country Profiles. Commonwealth Secretariat. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Bothwell, Robert (1996). History of Canada Since 1867. Michigan State University Press. pp. 31, 207–310. ISBN 0870133993.

- ↑ Bumsted, JM (1996). The Red River Rebellion. Watson & Dwyer. ISBN 0920486231.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Building a nation". Canadian Atlas. Canadian Geographic. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Sir John A. Macdonald". Library and Archives Canada. 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Cook, Terry (2000). "The Canadian West: An Archival Odyssey through the Records of the Department of the Interior". The Archivist. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). McClelland & Stewart. pp. 130–158, 173, 203–233, 258. ISBN 0771065140.

- ↑ Haglund, David G (1999). Security, strategy and the global economics of defence production. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0889118752. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedhail - ↑ Mulvale, James P (July 11, 2008). "Basic Income and the Canadian Welfare State: Exploring the Realms of Possibility". Basic Income Studies. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1932-0183.1084.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Goddard, Lance (2005). Canada and the Liberation of the Netherlands. Dundurn Press Ltd. pp. 225–232. ISBN 1550025473.

- ↑ Bothwell, Robert (2007). Alliance and illusion : Canada and the world, 1945–1984. UBC Press. pp. 11, 31. ISBN 9780774813686.

- ↑ Summers, WF. "Newfoundland and Labrador". Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Mackey, Eva (2002). The house of difference: cultural politics and national identity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 57. ISBN 0802084818.

- ↑ Landry, Rodrigue (May 2007). "Official language minorities in Canada: an introduction". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (185): 1–9. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.022. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Esses, Victoria M (July 1996). "Multiculturalism in Canada: Context and current status". Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 28 (3): 145–152. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Sarrouh, Elissar (January 22, 2002). "Social Policies in Canada: A Model for Development". Social Policy Series, No. 1. United Nations. pp. 14–16, 22–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Bickerton, James; Gagnon, Alain, ed. (2004). Canadian Politics (4th ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 250–254, 344–347. ISBN 1551115956.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- ↑ Légaré, André (2008). "Canada's Experiment with Aboriginal Self-Determination in Nunavut: From Vision to Illusion". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 15 (2–3): 335–367. doi:10.1163/157181108X332659.

- ↑ Munroe, HD (2009). "The October Crisis Revisited: Counterterrorism as Strategic Choice, Political Result, and Organizational Practice". Terrorism and Political Violence. 21 (2): 288–305. doi:10.1080/09546550902765623.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Sorens, J (December 2004). "Globalization, secessionism, and autonomy". Electoral Studies. 23 (4): 727–752. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2003.10.003.

- ↑ Leblanc, Daniel (August 13, 2010). "A brief history of the Bloc Québécois". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ↑ Betz, Hans-Georg; Immerfall, Stefan (1998). The new politics of the Right: neo-Populist parties and movements in ... St. Martinʼs Press. p. 173. ISBN 0312211341.

- ↑ "Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-06-22. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Sourour, Teresa K (1991). "Report of Coroner's Investigation" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "The Oka Crisis" (Digital Archives). Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). 2000. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Roach, Kent (2003). September 11: consequences for Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 15, 59–61, 194. ISBN 077352584X.

- ↑ "Canada and Multilateral Operations in Support of Peace and Stability". National Defence and the Canadian Forces. 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Jockel, Joseph T (2008). "Canada and the war in Afghanistan: NATO's odd man out steps forward". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 6 (1): 100–115. doi:10.1080/14794010801917212. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Canada: Geography". Country Profiles. Commonwealth Secretariat. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 "World Factbook: Canada". Central Intelligence Agency. May 16, 2006. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Territorial Evolution, 1927". National Resources Canada. April 6, 2004. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Susic, Stela (August 15, 2006). "Air Force becomes command authority for CFS Alert". The Maple Leaf. National Defence Canada. 12 (17). Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Significant Canadian Facts". Natural Resources Canada. April 5, 2004. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ National Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2005. p. 1. ISBN 0770511988.

- ↑ Bailey, William G (1997). The surface climates of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0773516727. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Etkin, David (April 30, 2003). An Assessment of Natural Hazards and Disasters in Canada. Springer. pp. 569, 582, 583. ISBN 9781402011795. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Tseax Cone". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. August 19, 2005. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Population Density, 2001". Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. June 15, 2005. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ The Weather Network. "Statistics, Regina SK". Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ "Canadian Climate Normals or Averages 1971–2000". Environment Canada. March 25, 2004. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Template:Cite document

- ↑ Smith, David E (June 10, 2010). "The Crown and the Constitution: Sustaining Democracy?". The Crown in Canada: Present Realities and Future Options. Queen's University. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-17. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 MacLeod, Kevin S (2008). A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1st ed.). Queen's Printer. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Template:Cite document

- ↑ "The Governor General of Canada: Roles and Responsibilities". Queen's Printer. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ Commonwealth public administration reform 2004. Commonwealth Secretariat. 2004. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0117032492.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Forsey, Eugene (2005). How Canadians Govern Themselves (6th ed.). Queen's Printer for Canada. pp. 1, 16. ISBN 0662396898. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-15. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille. "House of Commons Procedure and Practice: Parliamentary Institutions". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Prime Minister of Canada". Queen's Printer. 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Johnson, David (2006). Thinking government: public sector management in Canada (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. pp. 134–135, 149. ISBN 1551117797.

- ↑ Library of Parliament. "The Opposition in a Parliamentary System". Library of Parliament. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ O'Neal, Brian; Bédard, Michel; Spano, Sebastian (April 11, 2011). "Government and Canada's 41st Parliament: Questions and Answers". Library of Parliament. Retrieved 2011-06-02.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Hicks, Bruce M (2008). "Restructuring the Canadian Senate through Elections" (PDF). IIRP Choices. Institute for Research on Public Policy. 14 (14): 11. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Difference between Canadian Provinces and Territories". Intergovernmental Affairs Canada. 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "A Comparison of Provincial & Territorial Governments". Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Bakan, Joel (2003). Canadian Constitutional Law. Emond Montgomery Publications. pp. 3–8, 683–687, 699. ISBN 1552390853. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 Template:Cite document

- ↑ "Treaty areas". Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. October 7, 2002. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "What is Treaty 8?". CBC. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ McCormick, Peter (2000). Supreme at last: the evolution of the Supreme Court of Canada. James Lorimer & Company Ltd. pp. 2, 86, 154. ISBN 1550286927.

- ↑ "About the Court". Supreme Court of Canada. 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Sworden, Philip James (2006). An introduction to Canadian law. Emond Montgomery Publications. pp. 22, 150. ISBN 1552391450.

- ↑ Royal Canadian Mounted Police. "Keeping Canada and Our Communities Safe and Secure" (PDF). Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Haglung, David G (Autumn 2003). "North American Cooperation in an Era of Homeland Security". Orbis. Foreign Policy Research Institute. 47 (4): 675–691. doi:10.1016/S0030-4387(03)00072-3.

- ↑ James, Patrick (2006). Michaud, Nelson; O'Reilly, Marc J (ed.). Handbook of Canadian Foreign Policy. Lexington Books. pp. 213–214, 349–362. ISBN 073911493X.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- ↑ "About the Canadian Forces". Department of National Defence. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Teigrob, Robert (September 2010). "'Which Kind of Imperialism?' Early Cold War Decolonization and Canada–US Relations". Canadian Review of American Studies. 37 (3): 403–430. doi:10.3138/cras.37.3.403.

- ↑ Canada's international policy statement: a role of pride and influence in the world. Government of Canada. 2005. ISBN 066268608X. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Finkel, Alvin (1997). Our lives: Canada after 1945. Lorimer. pp. 105–107, 111–116. ISBN 1550285513.

- ↑ Holloway, Steven Kendall (2006). Canadian foreign policy: defining the national interest. University of Toronto Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 1551118165.

- ↑ Farnsworth, Clyde H (November 27, 1994). "Torture by Army Peacekeepers in Somalia Shocks Canada". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Canada and the Organization of American States (OAS)". Canadian Heritage. 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Opening Doors to Asia". Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Reichmann, Deb (July 7, 2011). "Canada ends combat mission in Afghanistan". Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ "Cost of the Afghanistan mission 2001–2011". Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ Konrad, Victor (2008). Beyond walls: re-inventing the Canada-United States borderlands. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 189, 196. ISBN 0754672026. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Vagnoni, Giselda (February 5, 2007). "Rich nations to sign $1.5 bln vaccine pact in Italy". Reuters. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Blomfield, Adrian (August 3, 2007). "Russia claims North Pole with Arctic flag stunt". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Row over Canada F-35 fighter jet order". BBC News. July 16, 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Bird, Richard M (October 22, 2008). "Government Finance". Historical Statistics of Canada. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Latest release". World Trade Organization. April 17, 2008. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Index of Economic Freedom". Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal. 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 "Imports, exports and trade balance of goods on a balance-of-payments basis, by country or country grouping". Statistics Canada. November 16, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Employment by Industry". Statistics Canada. January 8, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Easterbrook, WT (March 1995). "Recent Contributions to Economic History: Canada". Journal of Economic History. 19: 98.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Brown, Charles E (2002). World energy resources. Springer. pp. 323, 378–389. ISBN 3540426345.

- ↑ Clarke, Tony; Campbell, Bruce; Laxer, Gordon (March 10, 2006). "US oil addiction could make us sick" (PDF). Parkland Institute. Retrieved 2011-05-23.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Britton, John NH (1996). Canada and the Global Economy: The Geography of Structural and Technological Change. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 26–27, 155–163. ISBN 0773513566.

- ↑ Leacy, FH (ed.) (1983). "Vl-12". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ↑ Morck, Randall (2005). "Who owns whom? Economic nationalism and family controlled pyramidal groups in Canada". In Eden, Lorraine; Dobson, Wendy (ed.). Governance, multinationals, and growth. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 1843769093. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ Hale, Geoffrey (October 2008). "The Dog That Hasn't Barked: The Political Economy of Contemporary Debates on Canadian Foreign Investment Policies". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 41 (03): 719–747. doi:10.1017/S0008423908080785.

- ↑ "Jean Chrétien". CBC. July 13, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Sturgeon, Jamie (March 13, 2009). "Jobless rate to peak at 10%: TD". National Post. Archived from the original on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Canada has first yearly trade deficit since 1975". The Globe and Mail. February 10, 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Latest release from Labour Force Survey". Statistics Canada. November 6, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Yalnizyan, Armine (October 15, 2010). "The real state of Canada's jobs market". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "Budget fights deficit with freeze on future spending". CTV News. March 4, 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-21.

- ↑ "Canada's international investment position". The Daily. Statistics Canada. June 17, 2010. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Gross domestic expenditures on research and development". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Canadian Nobel Prize in Science Laureates". Queen's University. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ "Internet Usage and Population in North America". Internetworldstats. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Top countries in space sciences". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "The Canadian Aerospace Industry praises the federal government for recognizing Space as a strategic capability for Canada". Newswire. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Black Brant Sounding Rockets". Magellan Aerospace. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Canada on Mars?". Marketwire. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Beauchesne, Eric (March 13, 2007). "We are 31,612,897". National Post. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion Population 1971–2008 (pdf pages 83–85) IEA (OECD/ World Bank) original population ref e.g. in IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2010 page 57)

- ↑ Custred, Glynn (2008). "Security Threats on America's Borders". In Moens, Alexander (ed.). Immigration policy and the terrorist threat in Canada and the United States. Fraser Institute. p. 96. ISBN 0889752354.

- ↑ "Urban-rural population as a proportion of total population, Canada, provinces, territories and health regions". Statistics Canada. 2001. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ Martel, Laurent (September 22, 2009). "2006 Census: Portrait of the Canadian Population in 2006, by Age and Sex". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2009-10-18. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada – Data table". Statistics Canada. July 28, 2009. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ↑ "Aboriginal Identity (8), Sex (3) and Age Groups (12) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data". 2006 Census: Topic-based tabulations. Statistics Canada. June 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ↑ "One in 6 Canadians is a visible minority". CBC. April 2, 2008. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "2006 Census: Ethnic origin, visible minorities, place of work and mode of transportation". The Daily. Statistics Canada. April 2, 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ Pendakur, Krishna. "Visible Minorities and Aboriginal Peoples in Vancouver's Labour Market". Simon Fraser University. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ↑ "2006 Census: Immigration, citizenship, language, mobility and migration". The Daily. Statistics Canada. December 4, 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ↑ Lilley, Brian (2010). "Canadians want immigration shakeup". Parliamentary Bureau. Canadian Online Explorer. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ Friesen, Joe (March 9, 2010). "The changing face of Canada: booming minority populations by 2031" (Subscription required). The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Karla (2008). Canada (10th ed.). Lonely Planet Publications. p. 51. ISBN 9781741045710.

- ↑ "Canada's 2011 immigration level unchanged". CBC. November 2, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "When immigration goes awry". Toronto Star. July 14, 2006. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ "Government of Canada Tables 2011 Immigration Plan". Canada News Centre. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "Canada's Generous Program for Refugee Resettlement Is Undermined by Human Smugglers Who Abuse Canada's Immigration System". Public Safety Canada. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ↑ "Population by religion, by province and territory (2001 Census)". Statistics Canada. January 25, 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ "Overview of Education in Canada". Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. Archived from the original on 2010-01-05. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Creating Opportunities for All Canadians". Department of Finance Canada. November 14, 2005. Retrieved 2006-05-22.

- ↑ "Official Languages and You". Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. June 16, 2009. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ↑ "2006 Census: The Evolving Linguistic Portrait, 2006 Census: Highlights". Statistics Canada. 2006 (2010). Retrieved 2010-10-12. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ "Population by knowledge of official language, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. January 27, 2005. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Bourhis, Richard Y (May 2007). "Language planning and French-English bilingual communication: Montreal field studies from 1977 to 1997". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (185): 187–224. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2007.031. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Lachapelle, R (March 2009). "The Diversity of the Canadian Francophonie". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ↑ Hayday, Matthew (2005). Bilingual Today, United Tomorrow: Official Languages in Education and Canadian Federalism. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0773529608.

- ↑ Heller, Monica (2003). Crosswords : language, education and ethnicity in French Ontario. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 72, 74. ISBN 9783110176872.

- ↑ "Aboriginal languages". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G Jr. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (Web Version online by SIL International) (15th ed.). SIL International. ISBN 155671159X. Retrieved 2009-10-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ↑ Fettes, Mark (2001). "Voices of Winter: Aboriginal Languages and Public Policy in Canada". In Castellano, Marlene Brant; Davis, Lynne; Lahache, Louise (ed.). Aboriginal education: fulfilling the promise. UBC Press. p. 39. ISBN 0774807830. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ Russell, Peter H (2005). "Indigineous Self-Determination: Is Canada as Good as it Gets?". In Hocking, Barbara (ed.). Unfinished constitutional business?: rethinking indigenous self-determination. Aboriginal Studies Press. p. 180. ISBN 0855754664.

- ↑ "Population by mother tongue, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. January 27, 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ "First Official Language Spoken (7) and Sex (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas 1, 2001 Census – 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ "Canadian Multiculturalism" (PDF). Library of Parliament. September 15, 2009. pp. 1–7. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ↑ Franklin, Daniel P; Baun, Michael J (1995). Political culture and constitutionalism: a comparative approach. Sharpe. p. 61. ISBN 1563244160.

- ↑ Garcea, Joseph (January 2009). "Multiculturalism Discourses in Canada". Canadian Ethnic Studies. 40 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1353/ces.0.0069. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ↑ Bricker, Darrell; Wright, John (2005). What Canadians think about almost everything. Doubleday Canada. pp. 8–23. ISBN 0385659857.

- ↑ Magocsi, Paul R (2002). Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a short introduction. University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0802036309.

- ↑ Blackwell, John D (2005). "Culture High and Low". International Council for Canadian Studies World Wide Web Service. Retrieved 2006-03-15.

- ↑ "Mandate of the National Film Board" (PDF). National Film Board of Canada. 2005. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Brock, Richard (2008). "Envoicing Silent Objects: Art and Literature at the Site of the Canadian Landscape". Canadian Journal of Environmental Education. 13 (2): 50–61.

- ↑ Hill, Charles C (1995). The Group of Seven – Art for a Nation. National Gallery of Canada. pp. 15–21, 195. ISBN 077106716X.

- ↑ Newlands, Anne (1996). Emily Carr. Firefly Books. pp. 8–9. ISBN 1552090469.

- ↑ Dorland, Michael (1996). The cultural industries in Canada: problems, policies and prospects. J. Lorimer. p. 95. ISBN 1550284940.

- ↑ Edwardson, Ryan (2008). Canadian content, culture and the quest for nationhood. University of Toronto Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780802097590.

- ↑ "'O Canada'". Historica-Dominion. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ "Hymne national du Canada". Canadian Heritage. June 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ Wieting, Stephen G (2001). Sport and memory in North America. Frank Cass. p. 4. ISBN 0714682055.

- ↑ Conference Board of Canada (2004). "Survey: Most Popular Sports, by Type of Participation, Adult Population". Strengthening Canada: The Socio-economic Benefits of Sport Participation in Canada – Report August 2005. Sport Canada. Retrieved 2006-07-01. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "Vancouver 2010". The Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 193.0 193.1 Canadian Heritage (2002). Symbols of Canada. Canadian Government Publishing. ISBN 0660186152.

- ↑ Ruhl, Jeffrey (January 2008). "Inukshuk Rising". Canadian Journal of Globalization. 1 (1): 25–30.

Further reading[edit]

Template:Col-begin Template:Col-2

- History

- Riendeau, Roger E (2007). A brief history of Canada (2nd ed.). Facts on File. ISBN 9780816063352.

- Francis, RD; Jones, Richard; Smith, Donald B (2009). Journeys: A History of Canada. Nelson Education. ISBN 9780176442446.

- Taylor, Martin Brook (1994). Canadian History. 1 & 2. University of Toronto Press. Unknown parameter

|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) ISBN 0802050166, ISBN 0802028012

- Geography and climate

- Stanford, Quentin H, ed. (2008). Canadian Oxford World Atlas (6th ed.). Oxford University Press (Canada). ISBN 0195429281.

- Government and law

- Malcolmson, Patrick (2009). The Canadian Regime: An Introduction to Parliamentary Government in Canada (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442600478. Unknown parameter

|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Morton, Frederick Lee (2002). Law, politics, and the judicial process in Canada. Frederick Lee. ISBN 1552380467. Cite has empty unknown parameter:

|coauthor=(help)

- Foreign relations and military

- Granatstein, JL (2004). Canada's army: waging war and keeping the peace. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802086969.

- Economy

- Canada 2010. Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económicos. OECD economic surveys. 2010. ISBN 9789264083257.

- Demography and statistics

- Statistics Canada (2008). Canada Year Book (CYB) annual 1867–1967. Federal Publications (Queen of Canada).

- Statistics Canada (October 27, 2010). Canada Year Book. Federal Publications (Queen of Canada). Catalogue no 11-402-XPE.

- Culture

- Magocsi, Paul R (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's peoples. Society of Ontario, University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802029388.