The Game

The Game is a mental game where the objective is to avoid thinking about The Game itself. Thinking about The Game constitutes a loss, which must be announced each time it occurs. It is impossible to win most versions of The Game. Depending on the variation of The Game, the whole world, or all those aware of the game, are playing it all the time. Tactics have been developed to increase the number of people aware of The Game and thereby increase the number of losses.

Gameplay[edit]

There are three commonly reported rules to The Game:[1][2][3][4]

- Everyone in the world is playing The Game. (This is alternatively expressed as, "Everybody in the world who knows about The Game is playing The Game" or "You are always playing The Game.") A person cannot refuse to play The Game; it does not require consent to play and one can never stop playing.

- Whenever one thinks about The Game, one loses.

- Losses must be announced. This can be verbally, with a phrase such as "I just lost The Game", or in any other way: for example, via Facebook. Some people may have ways to remind others of The Game.

The definition of "thinking about The Game" is not always clear. If one discusses The Game without realizing that they have lost, this may or may not constitute a loss. If someone says "What is The Game?" before understanding the rules, whether they have lost is up for interpretation. According to some interpretations, one does not lose when someone else announces their loss, although the second rule implies that one loses regardless of what made them think about The Game. After a player has announced a loss, or after one thinks of The Game, some variants allow for a grace period between three seconds to thirty minutes to forget about the game, during which the player cannot lose the game again.[5][6]

The common rules do not define a point at which The Game ends. However, some players state that The Game ends when the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom announces on television that "The Game is up."[3]

Strategies[edit]

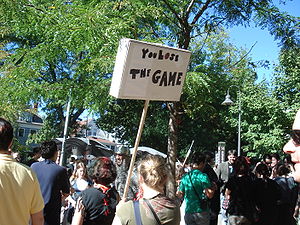

Strategies focus on making others lose The Game. Common methods include saying "The Game" out loud or writing about The Game on a hidden note, in graffiti in public places, or on banknotes.[2][7]

Associations may be made with The Game, especially over time, so that one thing inadvertently causes one to lose. Some players enjoy thinking of elaborate pranks that will cause others to lose the game.[8]

Other strategies involve merchandise: T-shirts, buttons, mugs, posters and bumper stickers have been created to advertise The Game. The Game is also spread via social media websites such as Facebook and Twitter.[8]

Origin[edit]

The origins of The Game are uncertain. In a 2008 news article, Justine Wettschreck says The Game has probably been around since the early 1990s, and may have originated in Australia or England.[9] One theory is that it was invented in London in 1996 when two British engineers, Dennis Begley and Gavin McDowall, missed their last train and had to spend the night on the platform; they attempted to avoid thinking about their situation and whoever thought about it first lost.[6][7] Another theory also traces The Game to London in 1996, when it was created by Jamie Miller "to annoy people".[5] Journalist Mic Wright of The Next Web recalled playing The Game at school in the late 1990s.[10]

However, The Game may have been created in 1977 by members of the Cambridge University Science Fiction Society when attempting to create a game that did not fit in with game theory. A blog post by Paul Taylor in August 2002 described The Game; Taylor claimed to have "found out about [the game] online about 6 months ago".[11] This is the earliest known reference on the internet.[5]

The Game is most commonly spread through the internet, such as via Facebook or Twitter, or by word of mouth.[8]

Psychology[edit]

The Game is an example of ironic processing (also known as the "White Bear Principle"), in which attempts to avoid certain thoughts make those thoughts more persistent.[6] There are early examples of ironic processing: in 1840, Leo Tolstoy played the "white bear game" with his brother, where he would "stand in a corner and not think of the white bear".[12] Fyodor Dostoyevsky mentioned the same game in 1863 in the essay Winter Notes on Summer Impressions.[13]

Reception[edit]

The Game has been described as challenging and fun to play, and as pointless, childish and infuriating.[5][6] In some Internet forums, such as Something Awful and GameSpy, and several schools, The Game has been banned.[2][7]

The 2009 Time 100 poll was most likely manipulated by the hacktivist group Anonymous, so that the top 21 people's names formed an acrostic for "marblecake also the game", referencing The Game.[14][15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Boyle, Andy (19 March 2007). "Mind game enlivens students across U.S." The Daily Nebraskan. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Rooseboom, Sanne (15 December 2008). "Nederland gaat nu ook verliezen". De Pers. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Three rules of The Game". Metro. 3 December 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ↑ "Don't think about the game". Rutland Herald. 3 October 2007. Unknown parameter

|subscription=ignored (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Montgomery, Shannon (17 January 2008). "Teens around the world are playing 'the game'". The Canadian Press.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kaniewski, Katie (1 March 2009). "You just lost the Game". Los Angeles Loyolan. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "If you read this you've lost The Game". Metro. 3 December 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Fussell, James (21 July 2009). "'The Game' is a fad that will get you every time". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Wettschreck, Justine (31 May 2008). "Playing 'The Game' with the other kids". Daily Globe. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Wright, Mic (13 April 2015). "You just lost The Game: the enduring hold of the pre-Web world's Rickroll". The Next Web. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ "The Game (I lost!)". 10 August 2002. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Tolstoy, Leo (2008). Leo Tolstoy, His Life and Work. p. 52. ISBN 1408676974. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014.

- ↑ Dostoyevsky, Fyodor (1863). Winter Notes on Summer Impressions. Vremya. p. 49. Italic or bold markup not allowed in:

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Schonfeld, Erick (27 April 2009). "Time Magazine Throws Up Its Hands As It Gets Pwned By 4Chan". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Marble Cake and moot". ABC News. 30 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2014. Unknown parameter

|deadurl=ignored (help)

External links[edit]

Media related to [[commons:Template:If then show|Template:If then show]] at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to [[commons:Template:If then show|Template:If then show]] at Wikimedia Commons- Template:Wikinews-inline